1. Importance of gender considerations for achieving health and nutrition outcomes for women and girls

Health is one of the key indicators of economic development of a family, community and nation. In addition to genetical conditions of individual or communities, economic status/poverty, availability and accessibility to quality health care services and resources, environment, and the social/community context are major determinants of health and nutrition outcomes (WHO). Gender disparity and gender inequality lies at the root of all these factors that causes differential/poorer health conditions of women, girls and children. There is ample evidence to inform the prevalent difference of health and nutrition outcomes between boys and girls or women and men. However, there is a major evidence gap to inform the impact of social/gender norms on the negative health status of women and girls. The role and influence of elements of her eco-system across her life cycle is also a critical gap area.

Despite India’s progress in reducing child mortality i, the benefits thereof have not been equally shared by the male and female child. According to the ‘Levels and Trends in Child Mortality’ report’ by the United Nations Inter-agency group for child mortality, fewer nations showed gender disparities in child mortality, & across the world, on average, boys have a higher probability of dying before reaching age-5 than girls. But this trend wasn’t reflected in India. India is among the few countries in the world where, the mortality under-5 years of girls, exceeded that of boys. This means that girls have a higher probability of dying before attaining the age of five years than boys. Through backward deduction, this means that effects of malnutrition are more pronounced for girls than boys ii . The root cause of such male-female differentials is the socio-cultural practices and mindset of the people which contribute to continued widespread prevalence of gender discrimination. Understandably, reducing the prevalence of malnutrition among girls holds the key to reducing the burden of female under-five deaths. Research shows that the girl child experiences mistreatment and neglect from the time of birth and thereafter during early childhood, facing a disadvantage in accessing nutrition and is thereby exposed to a higher risk of morbidity and mortality. Based on analysis of differential treatment of girls and boys in North India, Barbara Miller terms the prevailing anti-female bias as extended infanticide in her book ‘The Endangered Sex: Neglect of Female Children in Northwest India’.

Differential gendered treatment of boys and girls, impact their health (physical, emotional, social, spiritual and intellectual) and overall social upbringing negatively. Social norms of restricted and controlled environment of upbringing severely truncates their growth and development as a healthy holistic human resource. High degrees of morbidities start during adolescence. As per WHO, most of the adult life mental health disorders start at the age of 14, which go undetected and untreated. Iron deficiency anemia is one of the top causes of years lost by adolescents. Unhealthy food and nutrition availability and habits are foundation to sick adulthood for these adolescents. In all such situations, girls are further disadvantaged due to their weaker and lower social status.

Adult female members of the household also tend to be treated as inferior and receive a relatively lower share of nutrition and economic resources. In this context, maternal nutrition has significant carry-over costs as well. Undernourished girls grow up to become undernourished mothers and give birth to potentially undernourished, low-birth-weight children, who are more susceptible to death and disease. In fact, this potentially explains why India has the largest incidence of low-birth-weight children globally. If this inter- generational self-perpetuating cycle is not broken, the problem of malnutrition would continue to fester.

Multiple studies have also shown that the predicament of women is more pronounced for low-income households with strong ‘son’ preferences and a greater prevalence of gender-bias. Women in households continue the practice of eating last and leftovers iii , have little say in purchasing decisions of the households, limited access to mobility and therefore avail timely health services, and the list is long…. contributing to their poor health and nutrition status iv .

Gender norms, socialization, roles, differentials in power relations and access to and control over resources contribute to differences in vulnerabilities and susceptibilities to illness, how illness is experienced, health behaviours (including health-seeking), access to and uptake of health services, treatment responses and health outcomes.

2. Socio-cultural / Socio-ecological and other frameworks supporting gender issues

Gender roles and barriers owing to gender norms and other stereotypes have been put into certain frameworks by many agencies that guide program design and are used for various gender analysis and behaviour change frameworks and models. Two examples of such frameworks are below:

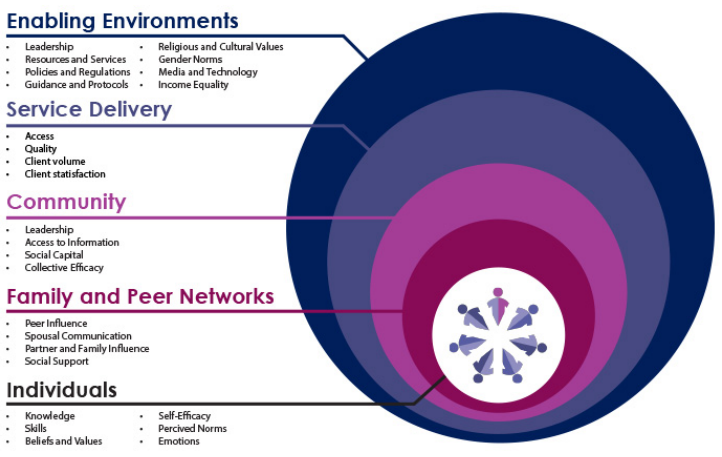

i) Socio-Ecological Model v

A person’s behaviour is influenced by many factors both at the individual level and beyond. The levels of influence on behaviour can be summarized by the socio-ecological framework. This framework recognizes that behaviour change can be achieved through activities that target four levels: Individual, interpersonal (family/peer), community and social/structural.

Figure 1: Socio-ecological model for health

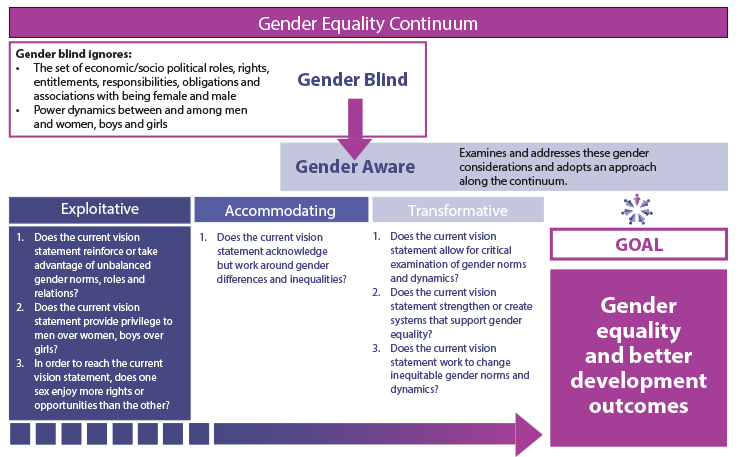

ii) Gender Equality Continuum

Behaviour Change Communication programs generally fit along the Gender Equality Continuum (IGWG, 2013), which can be used as a planning framework or as a diagnostic tool. As a planning framework, it can be used to determine how to design and plan interventions that move along the continuum toward transformative gender programming. As a diagnostic tool, it can be used to assess if, and how well, interventions are currently identifying, examining and addressing gender considerations, and to determine how to move along the continuum toward more transformative gender programming.

Figure 2:Gender Equality Continuum (IGWG, 2013)

The continuum shows a process of analysis that begins with determining whether interventions are gender blind or gender aware. Gender blind policies and programs ignore gender considerations. They are designed without any analysis of the culturally defined set of economic, social and political roles, responsibilities, rights, entitlements, obligations and power relations associated with being female and male, or the dynamics between and among women and men, girls and boys.

Gender aware policies and programs examine and address the set of economic, social and political roles, responsibilities, rights, entitlements, obligations and power relations associated with being female and male, and the dynamics between and among women and men, and girls and boys.

The process then considers whether gender aware interventions are exploitative, accommodating or transformative.

While selecting from a number of such frameworks available, it is important to consider following:

• What kind of health and gender-related outcomes are we looking to achieve?

• How does gender affect access and utilization of health/nutrition service delivery interventions?

• What kind of intervention, or combination of interventions across the levels of the socio-ecological model, are most likely to lead to gender transformative behaviours?

• How do we anticipate that women and men will understand these messages differently?

• How is men’s role to promote women’s health and well-being is being portrayed?

3. Gender in health and nutrition in development policies of India

Gender is a major determinant of health for women and men in India. Gender norms, roles and relations interact with biological factors, in turn influencing people’s exposure to disease and risks for ill health. Therefore, it is important for health policymakers to consider the different gender needs of all men and women. Tailoring health policies and programmes to take account of these differences and trends can improve their impact, reduce health inequities and advance the right to health for all. Health is significantly determined by social, economic, and environmental factors that lie beyond the health sector, such as poverty, education, employment and physical security. Gender inequality, an important determinant of health, remains a challenge in India, as elsewhere. Women lag behind men in many indicators of social well-being, such as literacy, opportunities to skill development and access to mass media. Women’s lower labour force participation and significantly larger time spent in unpaid care work also reflect gender inequality.

3.1. Gender in Health and Nutrition in the National Women Empowerment Policy of India, 2001

As far back as 2001, the Ministry of Women and Child Development, formulated a National Policy for Empowerment of Women where Health and Nutrition are mentioned as important levers for overall empowerment of women vi. The policy states that a holistic approach to women’s health, which includes both nutrition and health services will be adopted and special attention will be given to the needs of women and girls at all stages of the life cycle. This policy reiterates the national demographic goals for Infant Mortality Rate (IMR), Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) set out in the National Population Policy 2000. Women should have access to comprehensive, affordable and quality health care. Measures will be adopted that take into account the reproductive rights of women to enable them to exercise informed choices, their vulnerability to sexual and health problems together with endemic, infectious and communicable diseases such as malaria, TB, and water borne diseases as well as hypertension and cardio-pulmonary diseases. The social, developmental and health consequences of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases will be tackled from a gender perspective. Women’s traditional knowledge about health care and nutrition will be recognized through proper documentation and its use will be encouraged. The use of Indian and alternative systems of medicine will be enhanced within the framework of overall health infrastructure available for women. In view of the high risk of malnutrition and disease that women face at all the three critical stages viz., infancy and childhood, adolescent and reproductive phase, focussed attention would be paid to meeting the nutritional needs of women at all stages of the life cycle. This is also important in view of the critical link between the health of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women with the health of infant and young children. Special efforts will be made to tackle the problem of macro and micronutrient deficiencies especially amongst pregnant and lactating women as it leads to various diseases and disabilities. Intra-household discrimination in nutritional matters vis-à-vis girls and women will be sought to be ended through appropriate strategies. Widespread use of nutrition education would be made to address the issues of intra-household imbalances in nutrition and the special needs of pregnant and lactating women. Women’s participation will also be ensured in the planning, superintendence and delivery of the system

3.2. Gender in Health and Nutrition in the National Policy for Women, 2016

The Empowerment Policy was followed up by a National Policy for Women, which also elaborated on the operational strategies for these areas. It is laudable to find a continuity of the commitment to health and nutrition of women and girls from 2001 to 2016 through these policies. But, while the policies are progressive in ideas, it is more important to ensure that the ideas are operationalised. The inclusion of social and gender norms as the basis of understanding and addressing barrier women face would ensure a sound intervention design that will act across all levels of the eco-system, address all sorts of barrier and address any possible community and social backlashes. We need to ensure that the on-ground operations are sustainable in nature which allow women and the communities to continue their progressive shifts on their own.

3.3. Gender in The National Health Policy of India, 2017

Women’s Health & Gender Mainstreaming features as one of the important cross-cutting issues in the National health Policy, 2017. The policy states that while issues of women in reproductive age group are addressed through several programs, there will be enhanced provisions for reproductive morbidities and health needs of women beyond the reproductive age group (40+). Gender Based Violence is also recognized as a public health issue and public hospitals would be made more women friendly with staff oriented to gender – sensitivity issues. This policy notes with concern the serious and wide-ranging consequences of GBV and recommends that the health care to the survivors/ victims need to be provided free and with dignity in the public and private sector.

4. Gender addressal in health and nutrition programming

Despite the national policies mandating gender-based programming as part of all schemes and services, very few health and nutrition programs have taken a deeper dive into gender related issues to develop and implement a gender framework. It is commonly understood that a health program meant for women is naturally gender sensitive/transformative. However, most health programmes limit gender addressal to collection of gender disaggregated data, gender budgeting (assessed by the number of women reached) and conducting gender audits. It is seldom that a public health program, even one meant for women, actually addresses gender-based barriers.

As an example, a quick review of the flagship scheme for women Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) was undertaken. The JSY is a safe motherhood intervention that integrates cash assistance for with delivery and post-delivery care under the National Health Mission, India, with the objective to reducing maternal and neonatal mortality by promoting safe institutional delivery. By design, the scheme is for pregnant women from lower socio-economic strata of the society. It is assumed that provision of economic power to the targeted women will enhance their voice, choice and decision-making abilities. There is enough evidence to show substantial uptake of JSY leading to remarkable rise in institutional deliveries across the country, more so by the “at risk groups”. However, there remain pockets of poor performance of the scheme. A quick study of its implementation reveals that poor institutional delivery uptake is related to low literacy levels among young rural mothers, limited access of women to health care institutions and dependence on escorts, traditional health seeking behaviours of the family, socio-cultural factors, occupation and caste. A deeper look into these issues reveals a myriad of social norms that act as gender barriers, such as the influence of trusted sources of information on the woman (husband, mother-in-law, traditional healers, traditional birth attendants), gender roles within the household, lack of women staff at PHC‘s and their lack of sensitivity and insufficient numbers of ASHA workers to accompany each woman for delivery.

The operational guidelines of the scheme however do not touch upon these issues or ways to reaching out to these decision makers in a woman’s life. Though JSY is a part of gender transformative maternal health programme, there is a need to study how assets, women empowerment, occupation and decision-making power play a role in acceptance of JSY among more traditional families. To achieve higher intuitional delivery coverage in all regions and sustain the high levels, public health services need to direct interventions at changing social norms and breaking gender barriers.

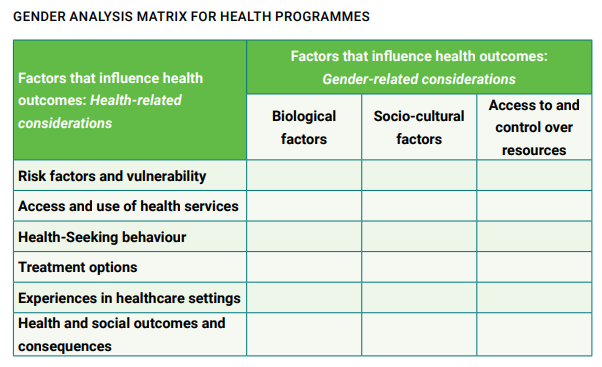

On the other hand, the National TB Elimination Program appears to be one of the few public health programs that has an exclusive Gender Responsive Framework in place that looks at an equitable, community led and gender specific response to TB in the country. The TB programme framework below can be seen as an example for integrating and analysing gender components as part of Health programming vii.

5. Suggested actions to address gender issues wholistically

A roundtable of public health practitioners was organized in November 2022, at New Delhi to initiate a discussion on gender barriers that impact health and nutrition outcomes and what platforms can and have been used to address these. Some of the discussion points are presented here.

The consensus of the group was that all existing public health and nutrition guidelines must be looked at with a gender lens and gender mainstreaming interventions need to be included at the formative stage itself. The group identified some simple and doable actions that can be adopted to address current gaps.

5.1. Address the gaps in Policy and Planning at the highest levels:

Several barriers to realizing gender equity, are related to policy and planning. To ensure gender mainstreaming in upcoming and existing health programs, a gender Nodal officer, who is also a gender Champion is needed at the level of the relevant Ministry. This Officer would bring together experts to ensure that gender related relevant points are embedded in each policy and all programmatic components. To do this, some suggested critical actions were –

• Formulation of a National Gender in Health and Nutrition Policy.

• Designated, trained Gender Nodal Officer in each relevant Ministry.

• Define and apply gender and social norms lens to each program

• Develop a Gender in health index to monitor the design, implementation and impact of programs

5.2. Identify and address gaps in services using a gender norms lens:

This refers majorly to supply related issues that impact uptake of services by women. Women’s awareness and their participation in local governance as peer/social pressure groups can help alter gender norms and align health and nutrition supply with demand. Existing Women’s collectives / SHGs / other groups can serve as a platform for ensuring this.

• Gender and nutrition are governed by behaviour, norms and power dynamics. An SOP on how to address these in households and communities may be worked out to optimise the demand for services with clear role of women’s groups.

• While working with women groups or SHGs, it is imperative to keep in mind that their work is aligned to the requirements and is leveraged with existing platforms on multiple health aspects.

• Conversations on health and nutrition should focus on overall life cycle of women and not remain focussed on maternal issues or see adolescent girls merely as future mothers.

• People in powerful roles, such as school principals, teachers, community influencers etc need to facilitate a change in gender dynamics and push for improved services and schemes through community platforms like Panchayat meetings, Gram Sabha, etc.

5.3. Role of local governance in improving male engagement

• Active participation of men and boys in family, neighborhood and community matters has the potential to bring about a change in policy, as in most parts of the country there are more men in positions of power and influence at both household and institutional levels and this is visible in Gram Sabha’s and PRI platforms.

• Special focussed efforts and innovative approaches are needed to include men in a systematic manner for societal gender norms to change.

5.4 Addressing gaps in assessment / monitoring

• Each of these programming aspects needs to be assessed through monitoring mechanisms.

• Concrete sex disaggregated and gender inclusive measurable indicators are important, and strategies at the district and below district level need to be thought.

• Health and Nutrition specific interventions are given by AHSA and AWWs, but indicators addressing gender specific and sensitive issues need to be understood and measured, which are equally important.

• Assessment should be around identified gender barriers to understand the progress of transition of such barriers to opportunities for improvement

6. Possible platforms through which gender issues / challenges and barriers can be addressed

1. Strengthen the Women’s Collective / SHG platform as a vehicle to bring about change in gender dynamics for health and nutrition in the household as well as community level. These collectives due to its strength of numbers and homogeneity are a critical source of social solidarity and resilience.

2. Leverage women’s groups in filling the gaps for awareness on health and nutrition, access to services, streamlining of services and community follow-up/rehabilitation to reinstate women in better health

3. Anchor gender within the policy and governance of the country for gender integrated planning of HN services, emphasizing the need for convergence between departments, specifically making gender considerations essential and uniform.

4. Promote convergence with PRIs and other platforms to engage men in conversations around gender and HN. This engagement should be built for a positive impact on addressing gender barriers that negatively impact the health and nutrition of women.

5. A learning collaborative of stakeholders can be formed for advocacy that could help in bringing priority on this subject. This will also help share and learn from each other since a lot of work is being done in this direction.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Social norms are the root cause of gender-based disparities in society. While delivering health and nutrition services, these norms must be well understood and all efforts made to address them. Health policy and programming should have components of social norm change to create an enabling environment to the messaging and services that are being provided. Forward-looking policies, if effectively implemented through suitable community and institutional mechanisms to mainstream gender will enable change towards greater equity. Several tools are available for gender analysis, assessment and planning or programming, which can help to identify gender inequalities in health and tailor the design, implementation and monitoring of health policies and programmes to take account of these differences, for improved outcomes. Additionally, using a human rights framework in health planning and policy making can help in identifying and adequately addressing the biological and sociocultural factors that differentially influence the health of men and women. Gender norms and socio cultural and ecological factors that are deep rooted in the country are serve as barriers to better Health and nutrition outcomes should be addressed through suitable platforms.The power of women’s collectives and the network of Self-Help Groups (SHGs) need to be harnessed to fasten the pace of the implementation of developmental solutions with deep impact at household levels for women’s empowerment and gender equality, equity.

- i https://www.unicef.org/reports/levels-and-trends-child-mortality-report-2020

- ii https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/a-gendered-view-of-indias-nutrition-strategy/article29433201.ece

- iii https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0247065

- iv https://feminisminindia.com/2020/06/26/gender-inequality-contributes-chronic-malnutrition-india/

- v https://sbccimplementationkits.org/gender/sbcc-gender-models-and-frameworks/

- vi https://wcd.nic.in/womendevelopment/national-policy-women-empowerment

- vii https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/388838054811%20NTEP%20Gender%20Responsive%20Framework_311219.pdf